“You were too young to remember.”

I have been told this throughout my life by my various family members, friends of family, and distant acquaintances that I didn’t even recognize. It took me years to realize that the statement was a wish — a desperate plea, a hopeful demand — but not the truth, despite my efforts to internalize it. As a child, I somehow recognized that simply nodding and avoiding eye contact would put the adults at ease when they made that conversation-ending claim. I did not want attention. I did not want pity. I did not want to cry, and I did not want to feel at fault when other people did. I didn’t know how to handle the glassy eyes and the cracking voices, so for years and years, I pretended that they were right. It was easier for everyone.

It’s taken me much more than half of my life to recognize that my silence was isolating. I didn’t believe that my experience mattered or that the aftermath of my family’s tragedy had a place for my voice. I felt like I had no right to partake in the grief since I had only a handful of memories of him, whereas everyone else had hundreds. I constantly belittled my own experience. I felt that I had nothing to contribute and nothing meaningful to say.

The first time I wrote about the experience of losing my father was in my undergraduate admissions personal statement in 2012. The piece described a magic trick I remember my dad performing in our family living room in Seattle, where he made a quarter disappear and then seemingly appear in my pocket. I used it as a metaphor for me discovering my interest in mechanical engineering. Choosing to write about that topic was difficult — I remember being told by school counselors during college advice panels that pity stories weren’t well received by admissions and death was a cliche topic. I chose to write about it anyway but was careful to speak about his passing in an almost blasé manner. It was no big deal, simply a passive plot point in my succinct life story. However misleading, it was ingrained in me from a young age that talking about loss was attention-seeking, and that was one reason I never spoke about it. Talking about it also made people visibly uncomfortable and profusely apologetic. In the end, I would end up being the one to comfort them or assure them that my dad having died when I was five was totally fine. I learned to be dismissive, sometimes even offering the idea that I didn’t remember much about him to make other people feel better. After many painfully awkward conversations, I learned my lesson. I used “parents” to refer to my mom and answered questions about my dad in the present tense. I did not want attention. I did not want pity. I did not want to cry, and I did not want to feel at fault when other people did. I was insecure about my own emotions and felt uncomfortable in my gray space of remembrance, not fully aware of what I was mourning, but not able to bury it completely either.

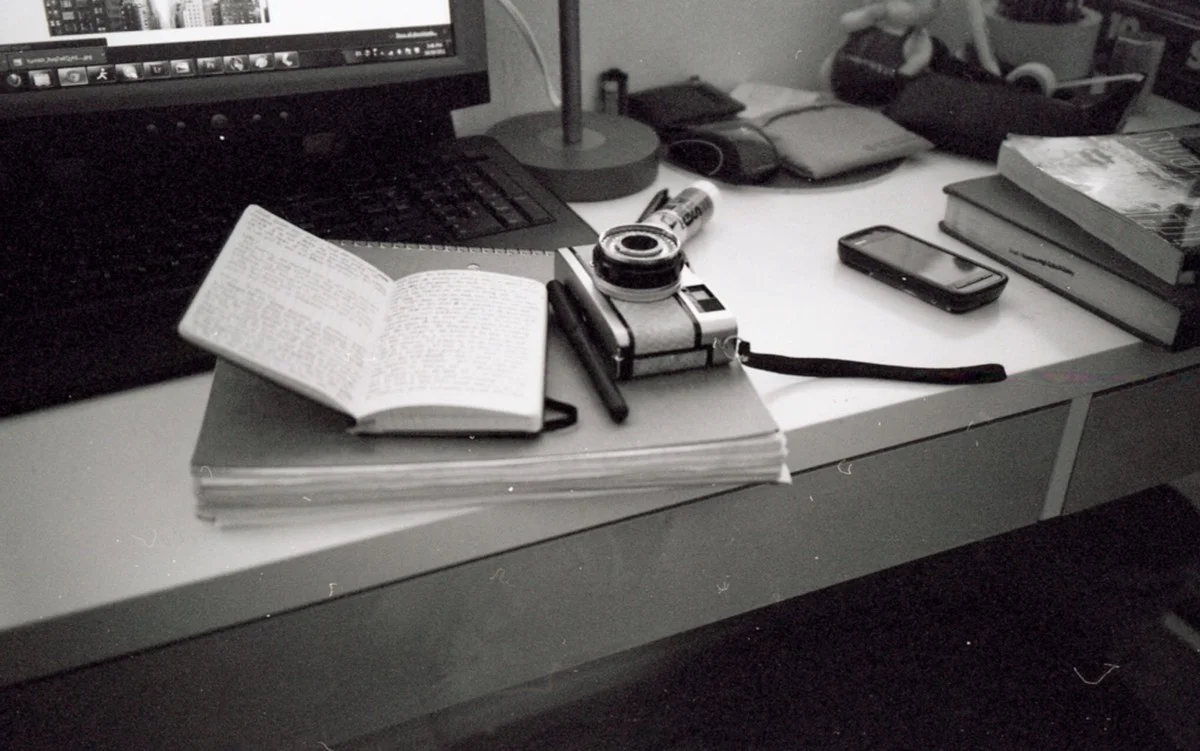

Growing up, I knew that my family was different, but my mom, despite all odds, provided me and my brother an unbelievably normal childhood. We played outside a lot, went to sleepovers, dragged ourselves to piano lessons, joined sports teams, dabbled in our hobbies, did well in school, and went on family road trips and vacations. Despite working late at night, my mom woke up before us every day to make us breakfast and lunch, and had dinner ready by the time we were home. She was critical but not naggy. She drove us to all of our commitments in addition to working all day. She trusted us with our own schoolwork and was entirely hands-off about academic performance. However, whenever we showed interest in particular hobbies, she was our biggest supporter. When I first started doing film photography, she would offer to take my rolls to Costco while I was at school and have them back by the time I was home, constantly feeding my excitement for grainy images from technology twenty years past its prime. She knew nothing about photography but regularly accompanied me to thrift stores to look for abandoned cameras. In Hong Kong, she bought me my first serious film camera, investing in my eye and inescapable urge to tell stories. Despite her consistent support in all aspects of my life, I never felt pressured to achieve anything in particular. I recognized that my happiness was a legitimate priority for not just my mom, but for my network of grandparents, uncles, aunts, and family friends. For that, I was, and am always grateful.

This unconditional and undying support was part of what made it difficult for me to bring up the times I felt sad, guilty, or lost. I was afraid that bringing up the ways in which I felt isolated would make my mom feel as if she didn’t do enough, when she had done so much more than I ever expected possible from someone in her position. I write about my experiences now not because I feel like I had a crippled childhood. I share my feelings now because I wish so desperately that I had other people to talk to about my experience when I was growing up. I wished I hadn’t accepted my own isolation, and I wish that by writing this, I will open a door for myself and for anyone who may share an even remotely similar experience.

After my father’s passing, I bounced around for a few years at different schools in the suburbs of Seattle until we moved to South Pasadena, California, close to my mom’s side of the family. I was ten. I would say that my experience there was fairly typical — I was occasionally made fun of for wearing ratty clothes, dressing like a boy, being vegan, or being stick skinny, but otherwise had a normal social experience. I drifted through various friend groups, survived the awkward middle school years, and fell in love with the tight bond of team sports. On the weekends and in the summers, I played basketball, practiced photography, went to the mall with my friends, read sad books, listened to sad songs, and watched sad movies. I wasn’t sad, but in retrospect, I was looking for relatable content and trying to create a reflection space for myself that didn’t involve talking about loss with other people.

I was drawn to books like Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (Jonathan Safran Foer), Looking for Alaska (John Green), Thirteen Reasons Why (Jay Asher), The Perks of Being a Wallflower (Stephen Chbosky), and Flowers for Algernon (Daniel Keyes). I kept a neatly organized Moleskine notebook full of quotes I came across, indulging in the authors’ painfully poetic words while I could conjure none for myself. My favorite movie, for as long as I can remember, has been The Lion King. It has wonderful music and amusing humor, but I know that I hold onto it dearly because it was the first movie I ever saw that dealt with the loss of a father.

“Look at the stars. The great kings of the past look down on us from those stars. So whenever you feel alone, just remember that those kings will always be there to guide you. And so will I.” — The Lion King

I’m not sure exactly how much that movie affected the way I view nature and the afterlife, but I do know that there are few things that comfort me more than lying down under a sky full of stars. I put up glow-in-the-dark stars in every single one of my rooms throughout my life until my first adult apartment, and I seek out stargazing opportunities at every given chance. In the shelter of my bedroom, under my plastic stars, I hid with the sounds and words from people I didn’t know instead of talking to people I did. I listened to songs like “If You Could See Me Now” (The Script), “Dead Hearts” (Stars), and “Shadow of the Day” (Linkin Park) to find relatable lyrics. I didn’t know what my friends and family thought of the books and music I immersed myself in, but I was content with letting it pass as teenage angst.

I tried, at various points in high school, to open up to my peers. In my sophomore year Spanish class, we had a Día de los Muertos activity for which our teacher asked us to bring an object to honor someone who had passed. I brought in my stuffed Winnie the Pooh — the last birthday present my father gave to me — ready to share a piece of myself, no matter how small. It was in pristine condition, mostly kept in a plastic bag since 2008, when I realized that dust and sunlight was discoloring its deep yellow fuzz. As I pulled the smiling bear from my backpack, a boy sitting nearby laughed at me and blurted out — “What the hell? Who died?” I felt tears spring to my eyes, but thought, for some inexplicable reason, that his privilege to make an insensitive joke transcended my right to be angry, and said nothing. As we sat in a circle on the floor of the classroom, my peers began taking turns talking about pets, grandparents, great-grandparents, or distant relatives that had passed. I don’t remember what I said in that class or whether I said anything at all. I only remember dashing out right as the period ended, hating myself for not having the courage to stand up to someone because they were popular and older and being terrified that he might apologize to me if I stayed. That class made me realize that I lived in a town where the death of a close relative was so improbable that a seventeen-year-old didn’t have to think twice before laughing at someone during Day of the Dead, and nobody, including the teacher, would confront him for it.

It was a few years before I felt that kind of spotlight again. It was Homecoming my senior year, which in my tradition-rooted school, required the fathers of the Homecoming Court to walk their daughters during the halftime show of the football game. I worked up to the courage to tell the supervising teacher that my father wasn’t in my life and asked if my mom could walk me. He said that might be “weird” and asked if I had any father figures in my life. It did not occur to me until then, but I didn’t. My brother, the most prominent male in my childhood, was studying abroad. My mom ended up walking me. I held my breath the entire night, hoping nobody would ask where my father was. Nobody did, but I felt like my family situation was highlighted in front of the whole school, and it compelled me to reflect on my life in a completely different way. I didn’t know how to reach out to my peers or how to talk about my experience, I just knew that I wanted to acknowledge what I felt, and for the first time, I wanted other people to acknowledge it, too.

On May 8th, 2013, the thirteenth anniversary of my father’s passing, something broke in me. I was simply incapable of pretending like it was a normal day. I couldn’t focus in school and wavered on the verge of tears. After class, I walked for nearly three hours, listening to Welcome Home (Radical Face) about 40 times until my legs could carry me no further. I sat on someone’s front lawn, watched sunlight stream through golden blades of grass, and cried. I was 18, and that was the first time I cried about my father’s death — I hadn’t cried at his funeral, I never cried when we visited him at the columbarium, I never cried on Father’s Day.

“You were never supposed to leave, now my head is splitting at the seams, and I don’t know if I can.” — Radical Face

I called my closest friend at the time, who was probably the first person I ever attempted to describe my experience to. She knew the day’s significance, since I had mentioned it earlier in our friendship. Despite knowing that her words would not help me, she met me on my way home to provide a hug that dissolved the wall I spent my whole life building. That was, as far as I can remember, the first time I ever explicitly reached out to someone for emotional support regarding an experience they were not part of. After that, I dragged myself home, and pretended it was just another day, just another year.

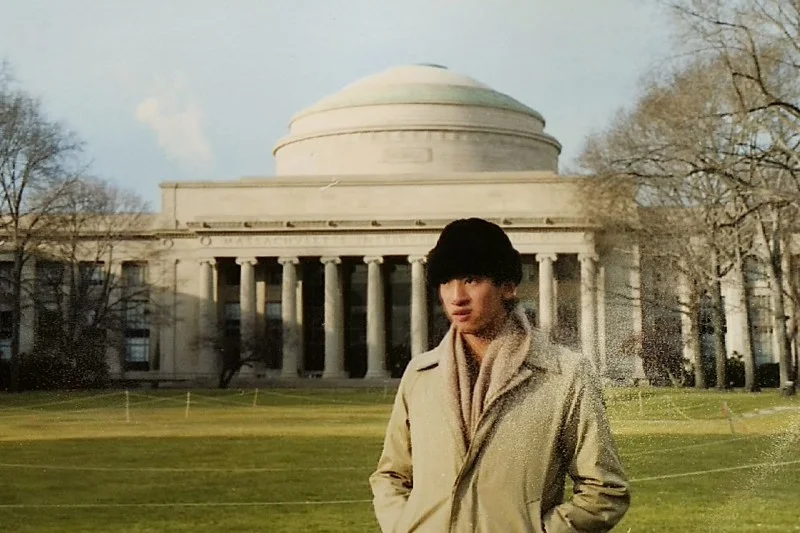

My wall continued to break down throughout senior year. On senior awards night, my grandma cried and said she wished my father could’ve been there to see me. On my graduation day, I felt distinctly empty, recognizing his absence at an important life event for the first time in my life. I burst into tears when my mom dropped me off in Boston, because I didn’t know how to tell her how grateful and proud I was for the life she provided me, because I missed her before she even left, because I felt guilty for moving so far away, because she had to fly home alone, and because I wanted to know how my father would have felt about me going to MIT, but I didn’t know how to ask.

I wrote a Medium post in 2016 which revolves around a memory I have of my father pulling me into his room to tell me, through gritted teeth, that I had to be “good” after he “left”. I had taken those words to heart, and spent a significant percentage of my life chasing a benchmark of good that I had established in his memory. I wrote that “I don’t think I’ll ever get to a point where I’m comfortable saying that my father would have been proud of who I am today. Maybe that’s stubborn, maybe that’s absolutely ridiculous, but maybe that’s the point. He left me with the challenge of the unobtainable.” I realize now how damaging that mentality was for the pursuit of my own interests. I graduated from MIT in 2017 with a degree in mechanical engineering with no desire to do mechanical engineering at all. It was getting that diploma, however, that made me finally realize that I had no right to determine what my father would have wanted from me.

Every single person’s experience of losing someone is different. My mom’s experience of losing a husband was drastically different than my grandma’s experience of losing a son. My brother’s experience, at eight, with more developed emotional awareness and a greater bank of memories, was different than mine. I couldn’t relate to everyone else’s experience of loss, centered around the parts of the multidimensional human they loved and missed, when my sense of loss was rooted in everything I didn’t know. I had no first hand grasp of my father’s personality. I didn’t understand the nuances of his character, didn’t know what made him happy, didn’t know what scared him, didn’t know what his favorite color was and didn’t have any understanding of his beliefs. I didn’t even have distinct memories of him speaking English. Nearly everything I knew about him was based on what people willingly told me, and to some extent, what I observed from our collection of family photos and videos. All of my prior expectations of myself were based on a few memories I have of being severely chastised as a child. I have only a small handful of normal memories of my father. I remember soaking stamps with him on our dining table for our stamp collection. I remember him handing me a stack of “scratch paper” for my army of origami seals, only later to find out that it hadn’t been scratch paper but a stack of my mom’s tax forms. I remember kicking soccer balls on our sloped backyard and trying to help him pull weeds from our lawn. I have memories of things that I regret — I’ve forgiven myself for most of them, considering I was barely five years old, but I still don’t play video games. My last memory of my father was when he called for me to visit him at his bedside in the hospital, but I didn’t go because I was too busy playing Pokémon on my GameBoy. I never saw him alive again.

I held onto these handful of memories alone for so long because I thought they were all I had. They felt uniquely mine in an experience that I felt alienated from, since by the time I was even beginning to process his loss, nearly twelve years had passed. I felt like I had to construct a version of him just based on a handful of memories alone — mine and the ones my mom and brother freely shared. What I created in my head was a two-dimensional imaginary tiger parent who had a wide variety of skills and hobbies. In truth, I had one great parent and a father I never knew. Knowing that and fully accepting it lifted a significant amount of pressure off of me. I felt better about pursuing a career that I wanted, not just one I thought my father would have wanted from me.

In July 2017, while on vacation in Southeast Asia with my brother and friends, I got a small tattoo. It’s not as impulsive as it sounds — I’ve wanted it since 2014, but decided to wait a few years to see if the desire would fade. It was the first and only significant decision I’ve ever made fully for myself. I knew that my mom would be upset but hoped that she would understand why I did it. I knew, based on what my family has told me, that my father definitely would not have approved. I got it anyway, because its purpose was to remind me that these expectations and beliefs I have about him are a construct of my imagination. The universe did not allow him time to watch me grow up or for shifting society to alter his opinions. Having the tattoo has helped me accept that fact and relieve my self-inflicted pressure, but it’s also been the biggest factor in enabling me to talk about him in normal conversations. Since it’s in a fairly visible location if I choose to show it, friends — both old and new alike — have asked me about its meaning. I was fairly reluctant to talk about it at first, scared that the topic would be too intense or would lead to awkward apologies again. Surprisingly, it’s been the opposite. It’s allowed me to talk about loss in a context where people expect significant meaning. It’s facilitated sincere discussions and provided opportunities for me to open up, which has been difficult for me throughout my life. I’m still nervous to reveal it to some family, wary of judgement or disappointment. In some cases, I find it difficult to talk to them about my father because I’m afraid of evoking painful memories, but I’m slowly pushing on those barriers as well.

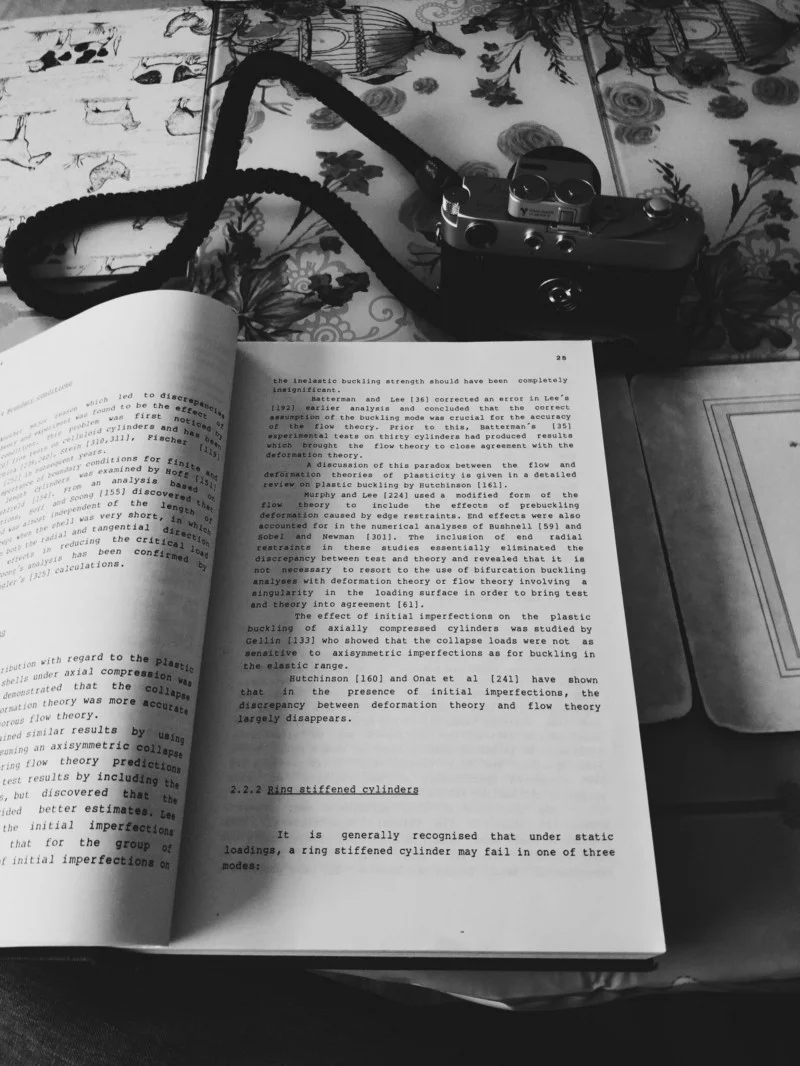

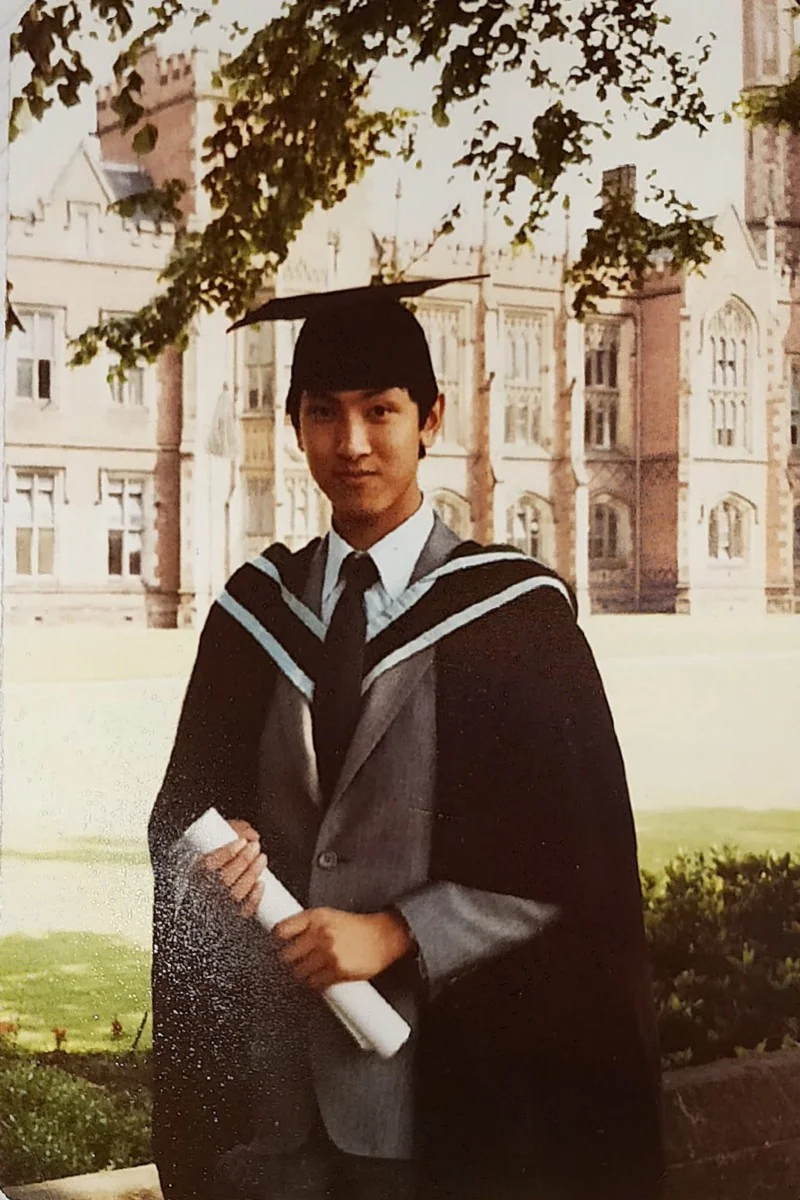

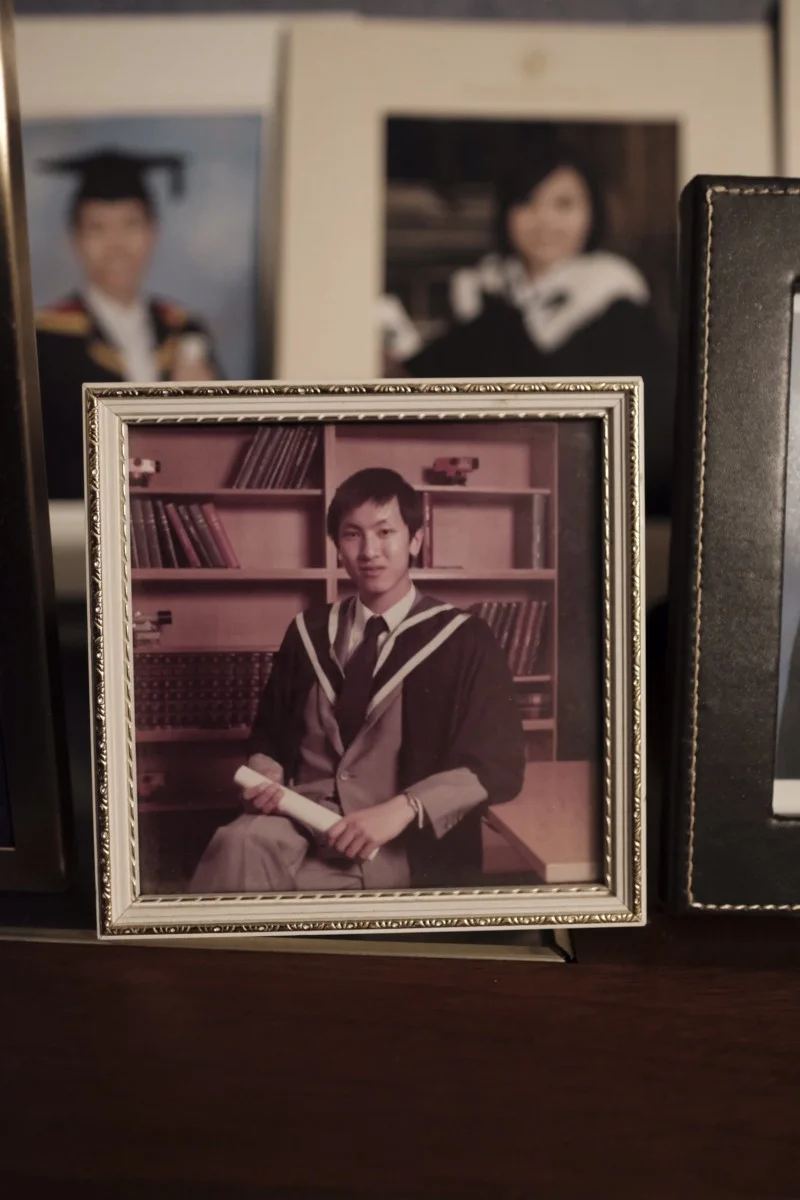

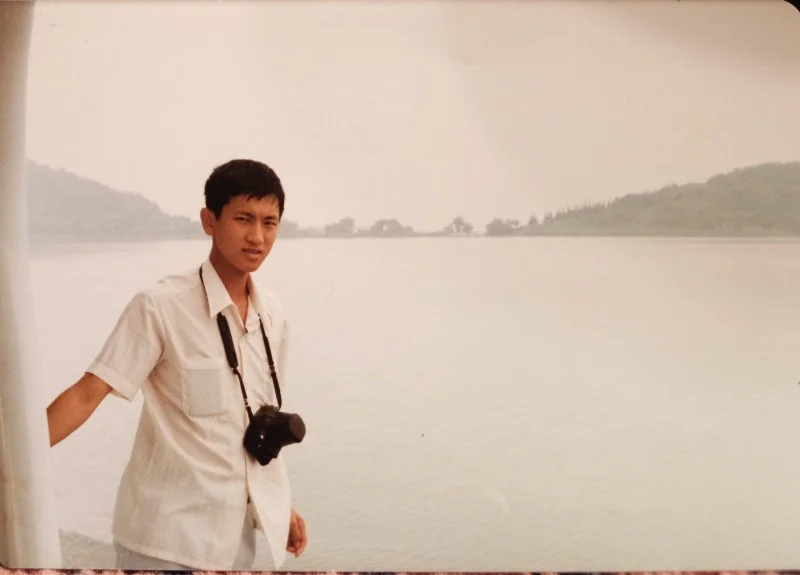

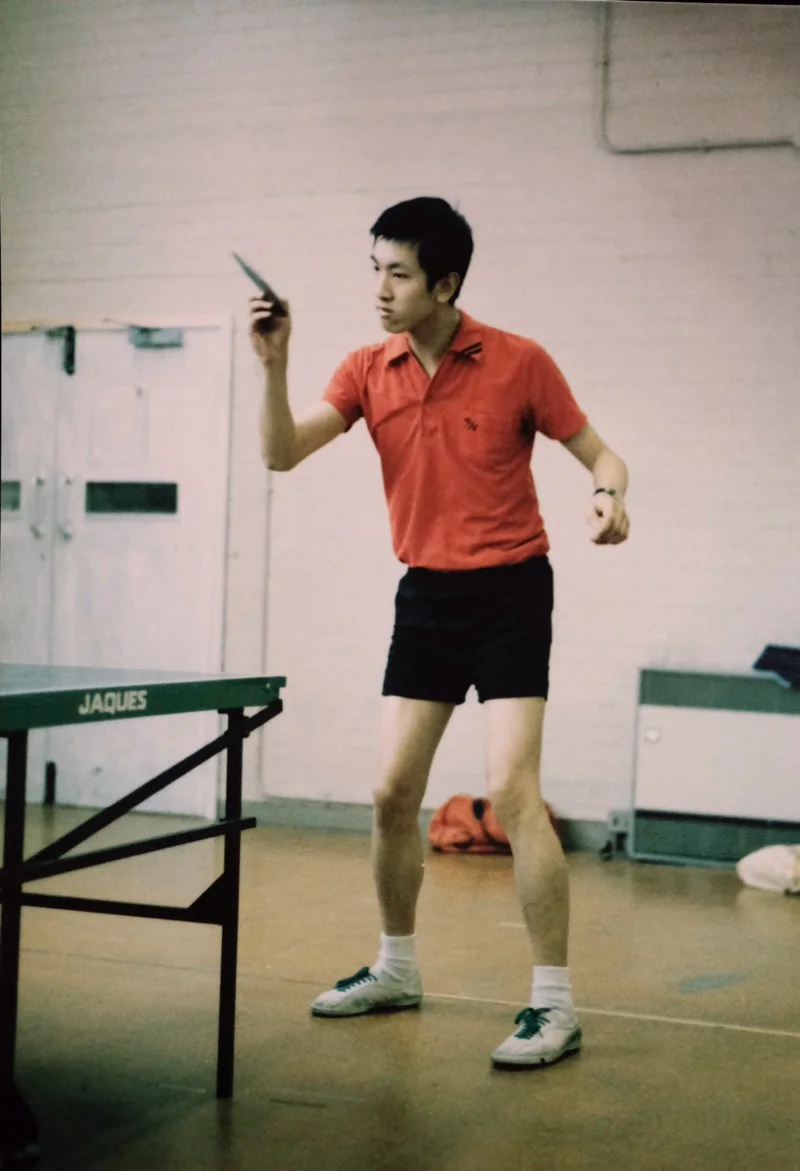

I went back to Belfast earlier this month. My father’s family moved to Northern Ireland in 1967 to open a Chinese restaurant, living there ever since. I visited for five days, and I spent most of it talking to my aunt about our family history and trying to gain a better sense of what it would’ve been like to grow up Chinese in Belfast during the 1960’s. My grandma brought out my father’s old briefcase, which contained hundreds of neatly stacked travel photos of him with his friends and family in Japan, Russia, China, and many other places I couldn’t identify in my short time there. I looked through pictures of him when he was my age and skimmed books he had kept — Japanese language learning books, structural engineering textbooks, and Chinese classics. My grandma found his PhD thesis from Imperial College in 1985, “Collapse of Ring Stiffened Cylindrical Shells Under Combined External Pressure and Axial Compression”. I read it, registering that I had never read his English writing before and that I liked his writing style. I also understood it. Despite the fact that I will probably never use my mechanical engineering education again, the degree was worth it if just for comprehending what my father dedicated four years of his research to. My aunt freely shared family stories, and I felt compelled to ask questions with difficult answers. My grandma was less willing to talk, but she showed her support for my curiosity by providing an endless supply of photos and allowing me to take some of them home. After a few days, I was off to London, where my father had moved to continue his education after receiving his B.S. in Civil Engineering at Queen’s University in Belfast in 1980.

When I got to London, a sincere friend accompanied me on an aimless adventure to find the structural engineering building at Imperial College. It took two trips and many flights of stairs due to my complete cluelessness about the campus, but we eventually found it. I imagined his life there, not as my father, but as a young, hopeful student with his life ahead of him. Where did he eat? Where did he relax? Did he take study breaks at the nearby museums? What were his friends like? Which halls had he walked in? Did he like his time there? I’ll never find the answers to these questions, but that’s okay. Spending time with cousins who were eager and willing to share their own memories of my father meant a lot to me. Simply existing in a city where he had spent formative years of his life meant a lot to me.

“You were too young to remember.”

I haven’t been told this in a long time, and I appreciate that. In truth, I probably remember a lot more than anyone expects, but not the parts people want me to. I remember watching the life drain out of him slowly. I remember our living room being littered with medical equipment. I remember the day the ambulance came and took him to the hospital on a stretcher. I remember finding his wispy hair on the ceiling of our car, right above the driver’s seat. I remember him losing his ability to speak. I remember the cremation. I remember climbing a ladder to put various objects he valued in with the urn at the columbarium. I remember not crying because I didn’t understand the concept of death.

My father’s death affected me more than his life did. That, perhaps, is the fundamental difference that makes it difficult for me to relate to other members of my family or even to other friends who have lost parents in more recent years. I could feel his love for me, but I wasn’t old enough to reciprocate. I didn’t necessarily miss him, but I longed for some understanding of what my life would have been like with him in it, or at least some understanding of him as a person. I wondered what it was like to have more than one parent, not because I felt like I needed another one, but because everyone else had two. My life was not changed by wisdom he imparted to me but by what I absorbed in watching a strong, healthy adult disintegrate right before my eyes as my primary introduction into the world. My understanding of life and morality is derived from my mom’s parenting and lessons learned, but I have a persistent gratitude for life that never leaves me — that’s what my father left me with. I feel a distinct heartache when something is too beautiful, whether that is an unforgettable sunset, an elaborate landscape, a meaningful friendship, an expertly weaved melody, or a delicious meal. I feel overwhelming gratitude for the smallest of actions, perpetually conscious of the fragility of human life and the way our existence and actions can affect others. I wrote, in 2016, that my father left me with “the challenge of the unobtainable”, but I realize now that’s not true. He left me with many things — love for analog photography, curiosity for science, affection for a yellow, midriff-baring bear — but most of all, he left me with an inexorable need to absorb and appreciate every moment of my life. Perhaps I was too young to remember him, but I feel his legacy every day in the way I am captivated by the world around me. I witnessed death before I even began to experience life, and while that may seem like a strange thing to be grateful for, I am.